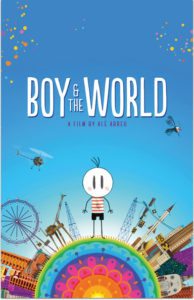

After I watched the first few minutes of Alê Abreu’s Boy and the World (Menino e o Mundo) I swore that I was going to love it unreservedly and that I was going to end up in tears.

After I watched the first few minutes of Alê Abreu’s Boy and the World (Menino e o Mundo) I swore that I was going to love it unreservedly and that I was going to end up in tears.

Neither prediction quite came to be, but it was a close call on both accounts.

Boy and the World is a film of images and emotions. There is a story, but only as much as your dreams tell a tale. A young boy’s father leaves to find work in the city. The boy follows him, or doesn’t, and finds him, or doesn’t, and through his travails he grows in some jagged, disconnected fashion that is hard to define or accept.

The beauty of the film, however; this is not hard to accept. It is animated as no other I’ve seen, in styles that leap from abstract to modern to digital to cubist to hallucinatory and on and on. The boy is only a stick figure. His striped red shirt is just horizontal lines of crimson that somehow, without substance, perfectly define a child. Watch him play in the trees and the streams. See him float on the clouds. Try to understand his confusion when his father is no longer there.

The beauty of the film, however; this is not hard to accept. It is animated as no other I’ve seen, in styles that leap from abstract to modern to digital to cubist to hallucinatory and on and on. The boy is only a stick figure. His striped red shirt is just horizontal lines of crimson that somehow, without substance, perfectly define a child. Watch him play in the trees and the streams. See him float on the clouds. Try to understand his confusion when his father is no longer there.

There is no decipherable language spoken or written in Boy and the World. People speak, and signs signify, but meaning is obfuscated by mirror-image letters that form words your brain struggles in vain to parse. If you turn on the subtitles, they simply say, “Foreign language.”

There is no decipherable language spoken or written in Boy and the World. People speak, and signs signify, but meaning is obfuscated by mirror-image letters that form words your brain struggles in vain to parse. If you turn on the subtitles, they simply say, “Foreign language.”

In the sky hang two moons. Other fractures of reality likewise tilt one continually off-kilter. But the boy — Cuca, the credits name him — he is very real. His feelings are barbed and they stick in you. You will be unable to remove them without suffering. It is better to let them bury in like shrapnel or splinters.

And the film does not walk a cheery, Disney path of struggle and redemption. The city Cuca falls into is cruel in the ways cities are. He finds men to care for him, in a sense, but they are incomplete and without voice. They are reflections in pools too easily disturbed.

And the film does not walk a cheery, Disney path of struggle and redemption. The city Cuca falls into is cruel in the ways cities are. He finds men to care for him, in a sense, but they are incomplete and without voice. They are reflections in pools too easily disturbed.

The film does not work towards themes of inner strength or adulthood claimed. It speaks of the abuse of labor, the illusion of materialism, and the loss of self. Music and color are battles to be won and lost.

In this way, and in many others, it is lovely and heartbreaking. To watch Cuca yearn in all his glorious innocence and to crumble is to remember what we’re better off forgetting.

In this way, and in many others, it is lovely and heartbreaking. To watch Cuca yearn in all his glorious innocence and to crumble is to remember what we’re better off forgetting.

What have we brought ourselves to with our questing and questioning? Can we go home? Is our father’s face there, waiting, or do we wear it now ourselves?

As it nears its conclusion, Boy and the World becomes all too real. It is a slap to both wake you and punish you. The end is not tragic, but if you don’t relive your own tragedies watching it, I wonder about who you are or will ever be.

As it nears its conclusion, Boy and the World becomes all too real. It is a slap to both wake you and punish you. The end is not tragic, but if you don’t relive your own tragedies watching it, I wonder about who you are or will ever be.

It is a film I’m glad to have seen. It is a film I will think about for a long time. I hear its perfectly hopeful, joyous, and mournful score now in my ears, reminding me to love my daughter, to never leave her, and to let her leave all the same when she must go.

This is the world we have made.

Another fairy-tale, and your recommendation is gorgeous. If the film approaches your encomium’s/elegy’s lyricism, it will be well worth the watching.

Which reminds me–I just watched this the other night. Very good. Thanks for the heads-up.

I am glad to have reached you both with this one. I think it deserves to live on a “10 Best Films You’ve Never Heard Of” list.