2016 has been a dirty knife in our hearts, but at least we still have Emma Stone.

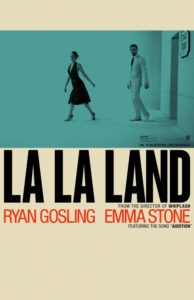

In Damien Chazelle‘s new neo-Musical, La La Land, Stone is a glass of bubbly and a long savored sip of peaty scotch. The rest of the film is also good — quite good in parts, and better than you might expect from its first frames — but seriously: all hail Emma Stone.

In Damien Chazelle‘s new neo-Musical, La La Land, Stone is a glass of bubbly and a long savored sip of peaty scotch. The rest of the film is also good — quite good in parts, and better than you might expect from its first frames — but seriously: all hail Emma Stone.

The year she dies will also fucking suck, just as 2016 has, but chances are it won’t also involve the election of an irradiated 1940s B-movie science fiction creature as president or the death of both David Bowie and Gene Wilder.

But La La Land. Over the past many years we have seen crashing waves of neo-Noirs, and neo-Westerns, and more remakes and ill-considered reboots than you can shake a cinderblock-filled dryer at. So why not a neo-Musical? MGM and other studios made sunshine with the genre long ago, and for logical reasons. Those being primarily that Musicals make us happy. They are a secret back door to the escape for which we’ve suffered and searched all day.

In general, I don’t particularly care for them, Musicals, but taste, exceptions, etc. Find me someone who doesn’t groove on at least parts of Singing in the Rain and I’ll find you someone you should immediately go about throwing in a cinderblock-filled dryer.

In general, I don’t particularly care for them, Musicals, but taste, exceptions, etc. Find me someone who doesn’t groove on at least parts of Singing in the Rain and I’ll find you someone you should immediately go about throwing in a cinderblock-filled dryer.

As the genre evolved over the decades, colors shifted and tones dropped. We got Bob Fosse — whose All That Jazz remains one of my favorites — and ’80s pseudo-grit such as Flashdance and Fame. Auteurs gave us weirdly luminous gems such as Rocky Horror and An American Astronaut. And through this chain, strands of intention and meaning trickled, drawing us in to varying degrees towards the sought after escape.

Damien Chazelle sees and understands this. In La La Land, he proves adept at wrestling the writhing snake into a tidy little bow. It is his third film (if you count his student effort) and his third centered on music, following the excellent torture porn romance of Whiplash.

But to the point: La La Land is a fanciful film about dreams, pursuit of success, and the price we pay for both. It begins with a traffic jam in Los Angeles. From cars, ordinary-appearing people step to sing and dance across hoods and with skateboards. In their bold, primary-colored shirts and skirts, they belt out their aspirations. It’s like a long commercial for Mentos and I, with jet-lag and caffeine battling it out inside me, felt afeared.

How Chazelle starts here isn’t bad per se but it’s also among the least effervescent things he does in the film. The opening number is a pin placed in an evolving map, offered to set your bearings. It is just set a tad assertively and you may feel a pinch.

How Chazelle starts here isn’t bad per se but it’s also among the least effervescent things he does in the film. The opening number is a pin placed in an evolving map, offered to set your bearings. It is just set a tad assertively and you may feel a pinch.

In this scene, we see (and hear) Chazelle address the hoi polloi, ourselves included. This will not be a film about a Julia Roberts character who happens to be a call-girl or about misunderstood geniuses played by Russell Crowe; it’s about you, and your dreams, and —most likely — specifically about Damien Chazelle and his dreams, which have to a great extent come true.

See the reviews for La La Land for proof.

So La La Land is a celebration of success and the turbulence that follows in its wake. I met Chazelle once, interviewing him before the release of Whiplash. In that film, Miles Teller plays a version of Chazelle. In this one, Ryan Gosling does, playing Sebastian, a jazz pianist. Chazelle — and Sebastian — are anxious and cautious; assertive despite self-protecting instincts that insist they’re about to be engulfed in flame.

But La La Land‘s ordinary folks — anxious and cautious; assertive and anticipating a coming conflagration — are not, by any stretch, ordinary. They are Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone and that’s both a problem and a Musical.

But La La Land‘s ordinary folks — anxious and cautious; assertive and anticipating a coming conflagration — are not, by any stretch, ordinary. They are Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone and that’s both a problem and a Musical.

Frankly, anyone who doubts Emma Stone’s Mia, an aspiring actress, will rise to great heights, must be a loon. Slightly less loony is buying into the inevitability of Gosling’s Seb, a man who’s been done wrong and who’s suffocating under his own ego and the insipid constraints of societal tastes. Seb longs to open a traditional jazz club where he can play what he wants, public opinion be damned.

The pair meet, and meet, and meet. Their animosity blossoms into affection and their banter into song. Through seasons, their relationship and their dreams wax and wane.

This is what Chazelle handles best. La La Land isn’t about how we grow strong together, or about how belting out our feelings on the freeway will armor us against life. It is about how we sell the dream to have the success. La La Land is about the melancholy, sacrificial, pyrrhic joy of becoming what you always imagined you wanted to be. That sounds glum, but it isn’t — anyone who’s grown up must understand. We achieve and, in achieving, change.

There is a reality to our lives that most musicals skirt, but not this one.

Not that Chazelle, who also wrote the script, skips the glittering, stagey, grand vistas and sets that make Musicals what they once were. All of that is there — the comic softshoe, the river of sequins, the two-dimensional Paris — but it is there as a reminder of how our dreams are dreams.

At its best, La La Land is ethereal. A scene in a movie theater of hands first held made me well up with the pure joy of romance released. Musical numbers — of which I wish there had been more, not less — blend into the story with the saucy elegance of, say, Debbie Reynolds. At other times, scenes drop like a wrong-footed, rattling beer bottle kicked down the raked floor of a cinema. While Emma Stone’s character gets a bright, goofy, fanciful introduction, Gosling’s gets a stone-cold doorstep turd.

At its best, La La Land is ethereal. A scene in a movie theater of hands first held made me well up with the pure joy of romance released. Musical numbers — of which I wish there had been more, not less — blend into the story with the saucy elegance of, say, Debbie Reynolds. At other times, scenes drop like a wrong-footed, rattling beer bottle kicked down the raked floor of a cinema. While Emma Stone’s character gets a bright, goofy, fanciful introduction, Gosling’s gets a stone-cold doorstep turd.

It’s a terrible scene and he’s terrible in it; looking even more so after the blinding glow of Emma Stone. He mopes around his sad apartment with his sister, named Exposition I’d guess, who harangues him and then never appears again.

But never mind. Once La La Land ensorcells you, so ensorcelled you shall remain. If you’re anything like me, you’ll forget the jet-lag and the caffeine and the death of all your heroes and the freezing wind and smile sadly, knowing both the electric excitement of what might have been and the solemn beauty of what is.

As I left the theater, well-satisfied, I glanced up to see the credits roll. Spread across the screen fell the name of David Wasco, production designer. Decades ago, when I was young and full of dreams and aspirations. I worked on a small film, as a personal assistant to the director. The production designer on that picture was David Wasco and I grew to be friends with him and his colleague and wife Sandy Reynolds-Wasco. David asked my opinion of a script he had been offered, one about which he was on the fence, and I encouraged him to take the gig. The script was Bottle Rocket. David — already the Production Designer who’d done Reservoir Dogs for Tarantino — became the go-to guy for Wes Anderson as well.

As I left the theater, well-satisfied, I glanced up to see the credits roll. Spread across the screen fell the name of David Wasco, production designer. Decades ago, when I was young and full of dreams and aspirations. I worked on a small film, as a personal assistant to the director. The production designer on that picture was David Wasco and I grew to be friends with him and his colleague and wife Sandy Reynolds-Wasco. David asked my opinion of a script he had been offered, one about which he was on the fence, and I encouraged him to take the gig. The script was Bottle Rocket. David — already the Production Designer who’d done Reservoir Dogs for Tarantino — became the go-to guy for Wes Anderson as well.

I worked on a few more films. David hooked me up with an interview once, a year or so later, with Lawrence Bender, to assist Tarantino on Four Rooms. I got the job, too, except Q’s old assistant came back around and they swiped the job back to give to her. I moved to San Francisco and left film production behind.

Or so my fuzzy recollection suggests.

Oh, what might have been. Oh, the dreams we sell to find the success we make. And then, when those dreams walk back in the door unbidden… what can we do but cherish the memory of how our hearts swelled?

If anyone has a line on David Wasco, please send him my sincere regards.