It took Martin Scorsese a decade to get The Last Temptation of Christ made, and it was shortly after its release that he was given Silence, the ’66 novel by Shūsaku Endō, a Japanese Catholic. It only took him twenty-eight years to make a movie out of it. The film deals with matters close to Scorsese’s heart: Faith, guilt, suffering. He subjects his characters to terrible spiritual and physical tests in order, one must imagine, to test his own faith against his doubts. In the end, faith wins. It always does, with the religious. Silence is made for believers. It shows that doubt will lead to compassion—so long as you never stop believing.

It took Martin Scorsese a decade to get The Last Temptation of Christ made, and it was shortly after its release that he was given Silence, the ’66 novel by Shūsaku Endō, a Japanese Catholic. It only took him twenty-eight years to make a movie out of it. The film deals with matters close to Scorsese’s heart: Faith, guilt, suffering. He subjects his characters to terrible spiritual and physical tests in order, one must imagine, to test his own faith against his doubts. In the end, faith wins. It always does, with the religious. Silence is made for believers. It shows that doubt will lead to compassion—so long as you never stop believing.

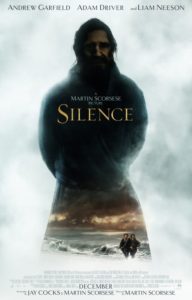

Set in 17th century Japan, Silence is primarily the story of one Portuguese Jesuit, Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield), who, with fellow Jesuit, Garupe (Adam Driver), travels to Japan in search of his mentor, Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson). Rumor has it that Ferreira apostatized and took a Japanese woman as his wife. The young Jesuits refuse to believe such a thing possible, and despite the dangers, find their way to Japan.

At this point in Japan’s history, Catholicism had been around for something less than a century, and more recently had been deemed illegal. Converts were tortured and/or killed and/or forced to renounce their faith, and so too the interloping Portuguese Jesuits. The movie opens with Ferreira watching his fellow Jesuits tortured to death. When Rodrigues and Garupe arrive, they’re the only two Jesuits in the country.

They’re surprised to find peasant Christians practicing in secret, but happy to offer their spiritual services. Soon the Christians are discovered, the Jesuits are captured, and the struggle of faith begins.

Rodrigues is faced with a kind of calm, reasoned evil in his Japanese captors. Governor Masashige (Issey Ogata), also known as the Inquisitor, explains that Catholicism won’t take root in Japanese soil, that it’s the equivalent of a bad foreign wife, and other meaningful metaphors. The Interpretor (Tadanobu Asano) accuses Rodrigues of being here not for the good of the people, but only to satisfy his own ego. Rodrigues tells them to go ahead and kill him, but the Japanese have come to understand the Jesuits all too well. Suffering, and dying, like Jesus before them, is their true goal. The Japanese will no longer reward them in so simple a manner.

Instead they want Rodrigues to do as Ferreira did before him, to apostatize. This is symbolized by stepping on a fumi-e, a small, carved image of Jesus, Mary, or other Christian iconography. Rodrigues, as one might imagine, struggles with the matter. It may only be a symbol, and his stepping on it only symbolic, but for a Jesuit whose life has been dedicated to his faith, apostasy is apostasy: It’s unthinkable. The mind of the Jesuit was not known for its flexibility on matters religious.

What’s at stake for Rodrigues isn’t just his own faith, it’s the fate of his new Japanese converts. They are being tortured by the Japanese. Many have been killed. Many more will be killed. It makes no matter to the Japanese rulers if these peasants renounce their faith. The faithful must see the Jesuit do it. By not apostatizing, Rodrigues would show his strength in Christ to his followers—but after giving them the opportunity to appreciate such heroic devotion, they will be tortured and killed. But by publicly apostatizing, the peasants will be granted freedom.

What’s a Jesuit to do?

Rodrigues is allowed to meet Ferreira, and this is where the movie lost me. I’d have expected Ferreira, having apostatized in order to end the suffering of others, to appear in some way enlightened, but instead he’s a beaten man. Indeed, the point is to show how the Japanese have broken him. When, in the end, Rodrigues does the same, he too, despite living a long life with a Japanese name and with a Japanese wife, is shown as sad and miserable and only going through the motions of his forfeit life.

Which is to say, he and Ferreira both get to have their cake and eat it too. They “renounce” their faith, thus ending the suffering of their followers, while essentially becoming martyrs in their own hearts. Look how they’ve suffered for others! They’re just like Jesus. Their only real regret, then, is having had the temerity not to die a martyr’s death.

To drive this home, at the very end of the film, when Rodrigues, old and gray, dies, and is given a fiery Japanese funeral, in one hand he’s holding a tiny wooden cross. You see, he never gave up his faith, not truly. The movie tells us that, indeed, his faith is all the stronger for having doubted it. (This addition is not in the book, which leaves the matter of what’s truly in Rodrigues’s heart at story’s end open to interpretation.)

Scorsese isn’t interested in what’s going on for the Japanese of this era. He allows solid arguments to be made by Rodrigues’s antagonists, yet they’re never presented as anything but antagonists. They’re the bad guys. I kept thinking of O’Brien from Orwell’s 1984 calmly explaining the reality of the world to that poor bastard Winston. He’s cool, logical, rational, and totally evil. So too are Masashige and the Interpretor. They’re insidious and calculating as they go about trying to destroy this godly man’s soul.

Arguing over whether or not poor, oppressed peasants will accept a religion that promises them absolution for every sin and everlasting life in paradise (hint: they will) is beside the point. What isn’t beside the point is whether or not cultural imperialists should be shown the door. I think it’s entirely reasonable that 17th century Japan would rather not have outsiders creeping in to their country and converting peasants to a foreign religion. I think merely calling Jesuits arrogant is being very, very kind. (Although, to be fair, torturing and murdering them swings the pendulum a wee bit far in the other direction.)

Silence does present two sides of this argument, but only as window-dressing to one man’s struggle. Rodrigues learns a lesson of humility—but he learns nothing about truth. He never stops believing there is only one truth, and that he possesses it. The Japanese may have forced him to renounce it in order not to bring suffering, but in his heart his beliefs never change. If anything, he’s stronger, and not because he’s seen another peoples’ point of view, but because of how very much he himself has suffered.

So, again, not a movie for heathen non-believers like myself. I’d love to see a movie that dealt with a Jesuit coming to understand that his truth is no better than that of the foreign culture he wants to convert, and that they have as much to teach him as he might have to teach them. But this is not that movie.

Silence has a lot going for it. This is Scorsese, after all. It looks fantastic. All greys and whites and blues and blacks, rocky coasts and mists, bamboo and blood and mud. His characteristic roving camera is nowhere to be seen. Taking a page from Japanese films, no doubt, he shows real restraint in how he chose to shoot the movie. This is serious, thoughtful material, and he comes at it with a feeling of great reverence.

Scorsese wrote the script with Jay Cocks (who co-wrote Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence and Gangs of New York as well). They manage to cover a lot of ground, but I couldn’t help feeling like I was on the outside looking in most of the time. The movie never bores, despite its length (161 min), but it does roll along on an even keel much of the time. The final segment, post-apostatizing, is narrated by Dutch trader Dieter Albrecht, who observes the sad ex-Jesuits in their miserable task of identifying Christian objects smuggled into the country by traders, and takes particular interest in Rodrigues.

I can’t say I’m a fan of Andrew Garfield in this movie. His is a role requiring depths of feeling he’s not able to convey. He really tries, though. Which is part of the problem. His first scene is striking, sitting beside his fellow Jesuit, played by Adam Driver. Driver is proving to be a great actor, and despite having a small part in Silence, the way he embodies his character merely by sitting is greater than anything Garfield achieves through all his suffering.

Even worse is when Garfield has to play against the Japanese actors, who are all excellent. He’s way out of his depth. He sits there looking like the cliché version of white Jesus, with his flowing locks of brown hair, and movie-star eyes, and it’s hard to feel he’s anything but what the Japanese think he is: An arrogant invader unwilling to learn a thing about the country whose people he wants to “save.”

I recall Garfield being quite good in the Red RIding Trilogy, but then it’s been a while and those films were unpleasant to be with.

This sounds like a good film for me to never quite manage to see despite voiced intention otherwise.

Watched it a couple of weeks ago. I found it a bit dry if I’m honest.

Andrew Garfield was miscast for this role. Putting aside the quality of his acting I felt he looks too young in the part which I found to be a problem. Reminded me of a similar issue with Jeremy Renner in American Hustle (incidentally a Scorsese knock-off film).

Yes, an actor with a little more life behind him would have aided this greatly.

They obviously aimed at epic on this one, but now I know that even Scorsese cannot make one without sufficient funding. Given they most certainly tried to follow Hollywood story structures here, it is clear the film has screenplay problems (budget limitations…) as the dramatic momentum starts to lag around the time Jesus Garfield is sent to jail. One would expect some further escalation after this, the clash of cultures or whatever, the rise of the stakes, the involvment of even more high ranking japanese officials, but instead we see more of suffering in the corner.

You are right, the japanese actors who are playing the roles of inquisitor (he did it a little over the top, kabuki style) and translator are both amazing, they outdid even Neeson. Garfield, while not delivering an enchanting performance, was quite good I think. Even in those cringe worthy moments of extreme emotion he’s not telegraphng the idea, he’s honest and thus, believable. Most certainly he found something in him to be able to play this part, but whether that was enough I’m not sure. It was extremely difficult role anyway and they had to have a young star to secure the financing. Driver was OK too, but his accent was not, neither was that ridiculous scene when they were dying to get out of that shed.