Jackie isn’t a biopic. It is, fittingly, a moment exploded into fragments. Director Pablo Larraín uses the film to stretch and elucidate the days following President John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Working from Noah Oppenheim’s script, he surmises how these moments and memories might have pierced Jaqueline Kennedy as a person, a political figure, a mother, and, now, suddenly and shockingly, a widow.

Jackie isn’t a biopic. It is, fittingly, a moment exploded into fragments. Director Pablo Larraín uses the film to stretch and elucidate the days following President John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Working from Noah Oppenheim’s script, he surmises how these moments and memories might have pierced Jaqueline Kennedy as a person, a political figure, a mother, and, now, suddenly and shockingly, a widow.

It is, in this way, quite fascinating.

It is also viscous, like congealed syrup. It starts and stops, edging towards something indeterminate. This is also fitting, I suppose, for its singular subject had far less to guide her actions than did the body politic. She could look back at the historical precedents set by Mary Todd — whose husband is remembered well — and at Ida Saxton, whose husband you likely cannot even name (that would be William McKinley) but her situation was and will remain unique.

Unlike either of those women or their husbands, the Kennedys lacked time in office to complete any signature political achievements. Their achievements were largely cultural, generational, and inspirational. So college dorms still get plastered with posters of JFK while Jackie remains a figure of renown in a way few first ladies are.

So who was this woman and why? This is what Jackie obliquely inquires.

Forget Zapruder and the rest; here is the real mystery of one of last century’s apex political events. It is a mystery of personality and also, to a degree, timing. In Jackie, the mystery of ‘what now’ is intimate and messy and slippery.

Forget Zapruder and the rest; here is the real mystery of one of last century’s apex political events. It is a mystery of personality and also, to a degree, timing. In Jackie, the mystery of ‘what now’ is intimate and messy and slippery.

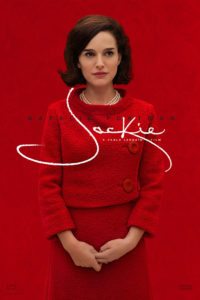

It is also flat, like a preserved flower trapped between two tomes. Natalie Portman’s performance in the titular role rolls between excellent and awkward. She juggles Jackie’s distinctive style of speech with inconsistent devotion, moving between imitation and homage. The script scrapes impressive details free and shakes them into a solution, but that solution never, for a moment, satisfyingly unclouds. One watches Jackie and knows Jackie far better than before, but also not at all. One understands the impact of President Kennedy’s assassination on a personal level, but not quite a visceral one.

The film left me feeling as if I’d met someone famous at a party, engaged her in private conversation, and then had her withdraw before a connection could be made. The questions I kept asking, she refused politely to answer.

Perhaps that’s simply the nature of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

So on the one hand, Jackie brings a resonant moment in American history to life in a way and from a perspective that adds depth and potency. On the other, its subject ends up remaining unilluminating — as if the filmmakers intended Jackie Kennedy not to be the subject of the film, but instead to serve as a catalyst for our own introspection.

On either account, I did not find Jackie wholly satisfying. It’s a curious film made a curious way about a curious transition in time, but its curiosity and mine remain unsated.