The problem with True Lies — an amped-up remake of the French film, La Totale! — is that Arnold Schwarzenegger being unmasked as a secret agent is as surprising a plot twist as Donald Trump turning out to be a nincompoop. If you didn’t see either reveal coming, one must question your powers of deduction.

Elliott Gould, though. That yegg is so deep undercover he’s still got his jammies on. He looks like a nebbishy, Jewish, insurance salesman. He talks like someone who really, really thinks you should try the gherkins. His is an inverted charm, so topsy-turvey and besquiggled that before you see it coming, it’s got you knocked up with a passel of little Gouldlets.

Elliott Gould, though. That yegg is so deep undercover he’s still got his jammies on. He looks like a nebbishy, Jewish, insurance salesman. He talks like someone who really, really thinks you should try the gherkins. His is an inverted charm, so topsy-turvey and besquiggled that before you see it coming, it’s got you knocked up with a passel of little Gouldlets.

Elliott Gould could steal the zipper right off your pants, mid bathroom break, without you even noticing. He probably already has. You should check.

Oh yes. Elliott Gould. You, without realizing it or admitting it, love him intensely. And that’s why he can rob you blind and leave you none the wiser. Which is precisely what he’s going to do in this long overdue Mind Control Double Feature.

The Silent Partner (1978)

I watch a lot of heist films. Most of them are unsurprising in their cadence. A group gets together to plan and stage a robbery. It all ALMOST goes off perfectly, or there’s an unsurprising surprise betrayal at a key moment, or the plan gets abandoned at the last second in favor of hooking up an 8′-square steel vault to a couple of American muscle cars so they can drag it through the streets of Rio.

You know the drill. It’s a good drill, but still: it’s rare to have a heist film sneak in sideways to slap the arched eyebrows off your face.

The Silent Partner sneaks in sideways. Then it makes off with your eyebrows.

It is not a glamorous film. It is not a film that betrays an overabundance of technical savvy or awareness of interpersonal norms. The acting is hobbled by the dialogue in a hit & miss script — adapted from the original Danish story by Curtis Hansen, who went on to helm Wonder Boys and L.A. Confidential among others — that intersperses crafty ploys with stock genre shorthand.

It is not a glamorous film. It is not a film that betrays an overabundance of technical savvy or awareness of interpersonal norms. The acting is hobbled by the dialogue in a hit & miss script — adapted from the original Danish story by Curtis Hansen, who went on to helm Wonder Boys and L.A. Confidential among others — that intersperses crafty ploys with stock genre shorthand.

And yet sideways The Silent Partner sneaks.

Set in Toronto (one of the first films to take advantage of Canada’s tax incentives for filmmaking), in a generic shopping mall bank, this is a heist film unlike any other. For one: it stars Elliott Gould. Gould plays vault teller Miles Cullen, a jovially awkward man, like, say, Elliott Gould, who collects tropical fish and studies chess (see above note in re: genre shorthand). Cullen works in a bank with Susannah York‘s Julie and John Candy’s Simonson (yes, that John Candy).

Because Miles Cullen is both observant and lucky, he becomes aware that the mall’s Santa Claus (Christopher Plummer; Harry) is staking out the bank in preparation for a robbery.

And so Miles does what anyone else would. He bides his time until the robbery is imminent, hides his till’s outsized wad of cash in a Superman lunchbox, and then he lets the robbery go off as planned. Harry gets away with chump change while Miles — brave, heroic Miles — goes home with about $50,000.

Pretty slick, right? Is your zipper still on your pants? Better look again.

Now. The Silent Partner fails to completely live up to the promise of this inspired premise. There is some odd romance. There is some feint-filled cat & mouse with the sadistic Harry, who’s well played by Plummer. And there is some unnecessary sexual violence and casual misogyny that really should have expired well before the 1970s.

That said: The Silent Partner inspires one to rob banks. Or, at least, pre-Michael Mann banks. (Do they still have any of those? Maybe in Canada?)

The trick, it seems, is simply being Elliott Gould. And trust me, I’m working on it.

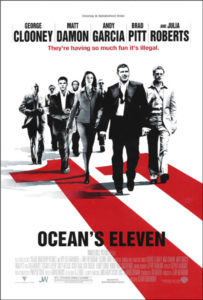

Ocean’s Eleven (2001)

While George Clooney‘s Danny Ocean is the eponymous star of Ocean’s Eleven — and the next two films in the series — if it weren’t for Elliott Gould’s Reuben Tishkoff, the whole crazy caper would be kaput.

While George Clooney‘s Danny Ocean is the eponymous star of Ocean’s Eleven — and the next two films in the series — if it weren’t for Elliott Gould’s Reuben Tishkoff, the whole crazy caper would be kaput.

That’s because it takes a Gould to steal the unstealable. One must have a partner — silent, near-suicidally crazy — willing to put life and livelihood on the line. This is what Reuben does. He puts up the funds so that Danny, Rusty, and the rest can risk their necks (and his) to make off with a fortune. And, not incidentally, embarrass Terry Benedict (Andy Garcia), who made the mistake of disrespecting Reuben, in the process.

Now, Ocean’s Eleven is far from my favorite Steven Soderbergh film. Others here would even say it isn’t the best of Soderbergh’s Ocean’s trilogy — a point I politely disagree with. But, none-the-less, it is an excellent film. It is a film of supremely satisfying neatness. It is an atomic clock made of insouciance. It is exactly what Hollywood, at its best, sets out to create.

It is like someone whispered a box-office fever dream to Soderbergh and our Steve looked it up and down, made some off-the-cuff edits, and rocked it out one-handed while whistling some Sinatra. Ocean’s Eleven is a film that can be watched at any time, in any company, from any point, for any length of time.

It is like someone whispered a box-office fever dream to Soderbergh and our Steve looked it up and down, made some off-the-cuff edits, and rocked it out one-handed while whistling some Sinatra. Ocean’s Eleven is a film that can be watched at any time, in any company, from any point, for any length of time.

Except for some of the scenes with Don Cheadle‘s Basher Tarr. I mean, I love me some Cheadle but that character blows.

If you haven’t watched Ocean’s Eleven, you’ve missed one of the modern era’s landmark heist films. It is the benchmark that countless others attempt — and fail — to reach. It isn’t surprising in the way The Silent Partner is, and its cadence isn’t unusual; it’s just so perfectly timed that you have to follow it’s lead.

I suppose that makes Ocean’s Eleven the Fred Astaire of caper pictures.

While Elliott Gould isn’t in it a whole lot, he’s Elliott Gould. He can do a lot with less. He can make you rob his bank, or his casino, and he can walk away with the loot. Because he’s Elliott Gould.

And someday soon, I will be, too.

Say, I recently watched The Silent Partner too. Yep, pretty good for a low key ’70s heistish Gould flick. And with bonus John Candy too.