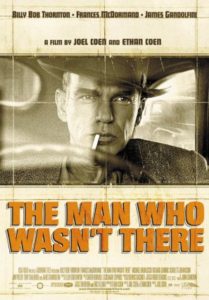

Life is a death sentence. I think that about sums up the theme of the Coens’ neo-noir The Man Who Wasn’t There (’01). Their lone excursion into black and white is a stark affair, narrated with zero affect by Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton), a barber in late ‘40s Santa Rosa. It’s a beautifully bleak movie, with a classic noir protagonist in Crane, doomed from the outset, smoking a crackling cigarette in every scene, doing little but waiting for the inevitable axe to fall.

Life is a death sentence. I think that about sums up the theme of the Coens’ neo-noir The Man Who Wasn’t There (’01). Their lone excursion into black and white is a stark affair, narrated with zero affect by Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton), a barber in late ‘40s Santa Rosa. It’s a beautifully bleak movie, with a classic noir protagonist in Crane, doomed from the outset, smoking a crackling cigarette in every scene, doing little but waiting for the inevitable axe to fall.

Watching it for the first time in a decade, I found its slow, grim pace and haunted cinematography (by Roger Deakins, channeling the ’40s greats) more or less delightful. Thornton plays Crane like a rock. I’m hard pressed to say if a single expression crosses his face. He narrates the film from, we learn by the end, jail, and does so with a detached perspective on all that brought him there.

Thing is, I don’t think his perspective is any less detached while the events are happening. He’s a passionless man who for the most part watches events take place around him, rarely taking action, and taking it when he does without any real desire or need.

This is unusual for noir. For The Man Who Wasn’t There, I think it’s what keeps the movie at a distance, what keeps it from connecting in the way the Coens’ best movies, and the best noirs, connect.

Film noir is a bleak distillation in dramatic form of life itself. In noir, a character makes a choice—usually to steal money or chase after love, or both—and that choice dooms them. They struggle to stay alive for the duration of the movie, but we know they won’t make it. They know too. Their fate is sealed from the beginning. So, life. We’re none of us making it out alive, no matter how hard we struggle, but by god we’ll struggle right to the bitter end.

What dooms noir protagonists is desire. They desire money, they desire love. Their desires destroy them. It’s the human condition writ small.

Desire is what’s missing from The Man Who Wasn’t There. Ed Crane the barber isn’t especially happy with his life, and when a man needing money to start a dry cleaning business drops by the barbershop, Ed figures he can get the ten thousand by blackmailing his wife’s boss. The pair are having an affair, so it’s two birds with one stone—he gets the money to maybe buy his way out of the barbering business and into a different life, and he gets to screw over the guy sleeping with his wife.

Only he just doesn’t seem to care much about any of it. He’s not out for a big score. He just figures why not, maybe it’ll work, but probably it won’t. He doesn’t care if his wife is sleeping around. He’s not sleeping with her. He’s a blank slate with no desire to fill himself in.

The character has a lot in common with Ray from the Coens’ Blood Simple. Ray too says little and shows scant emotion. It’s a type the Coens are drawn to. Only Ray is introduced driving through the rain with the married woman he’s having an affair with. Passion is implicit, no matter his few words on the matter. His is a noir fate we can feel. By the end, he’s a mess. He’s wracked with fear and desire.

Ed Crane, not so much. Ed doesn’t feel a damn thing. Once his ill-fated scheme is set in motion, he doesn’t do much to stop it. He accepts it, mostly, or reacts when pressed. It gives him pause, the pain and suffering he’s caused. He’s given to deep thoughts about life and fate, like so many Coens protagonists before (and after) him. But he’s content to watch his fate unfold without his having anything to do with it.

In a way, Ed is like a man who knows he’s in a noir, who knows struggling is pointless, he’s doomed no matter what, and so does nothing. Thematically, it’s an interesting angle to take. Philosophically too—if struggle is futile, why struggle? Emotionally, it generates nothing at all.

Maybe this is why the Coens shoehorn UFOs into the story. It’s the ‘40s, Roswell is in the newspapers, it’s not totally out of place. It’s a very Coens move. But it does feel shoehorned. It feels like they’re trying to say something about a fate we have no control over—maybe aliens are behind our suffering!—but without going all the way with it. It comes across as weirdness for the sake of something weird in an otherwise very low-key movie.

The Man Who Wasn’t There may be the Coens’ bleakest movie. Which is saying something. They take the standard message of noir—No matter how hard you struggle, you can’t escape your fate—and change it to: You can’t escape your fate, so why bother trying?

I bought this on DVD back when I used to buy weird movies none of my friends liked. I haven’t watched it since but I took it out of a box of DVDs a few weeks ago. Maybe revisit it. I just remember scene where a car flies through the air.

Definitely worth re-watching. There’s a lot to appreciate. The performances are across the board fantastic. And every shot is lovely. It’s just that maybe in the end you never feel anything but the same kind of apathy as does poor old Ed Crane.