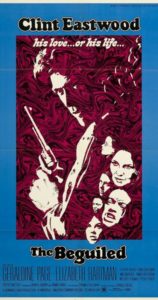

The Beguiled (’71) is as strange a movie as Clint Eastwood ever starred in. He made it with an eye toward expanding his acting range and playing a non-heroic part. Box-office-wise, it flopped, but artistically it was a watershed for Eastwood as actor and Don Siegel as director. It’s strange and gothic and melodramatic and dark. Universal didn’t know what the hell it was, so failed to market it beyond plugging Eastwood with a gun and a houseful of buxom beauties. It tanked in the states, but cleaned up in France. Go figure.

The Beguiled (’71) is as strange a movie as Clint Eastwood ever starred in. He made it with an eye toward expanding his acting range and playing a non-heroic part. Box-office-wise, it flopped, but artistically it was a watershed for Eastwood as actor and Don Siegel as director. It’s strange and gothic and melodramatic and dark. Universal didn’t know what the hell it was, so failed to market it beyond plugging Eastwood with a gun and a houseful of buxom beauties. It tanked in the states, but cleaned up in France. Go figure.

It’s now been remade by Sofia Coppola, who was named Best Director at this year’s Cannes Film Festival for her trouble (making her only the second woman ever to win the award). She says she wanted to tell the story from the point of view of the female characters. I haven’t seen her version (Stand By For Mind Control has yet to be invited to Cannes), but this is a strange way to put it. Maybe what she means is she wanted to tell a story more sympathetic toward the female characters. In Siegel’s version, one is meant to side with Clint, yet much of the story we see through the eyes of the women. We hear their inner thoughts in voice-overs, and as for Martha (Geraldine Page), at whose girls’ school the movie is set, we see flashbacks of her incestuous relationship with her brother. For her version, Coppola dropped the voice-over and the backstory.

She also dropped the one slave character, Hallie (Mae Mercer in the original), saying she didn’t want to have a slave if she was going to treat the subject lightly. I’m not sure what’s forcing her hand on the matter of how to deal with slavery, but in the original, Hallie is a key character, the first of the women Clint’s John McBurney tries to get on his side, seeing as he’s fighting for her freedom (or so he suggests, hoping to win her sympathy). Setting a movie during the Civil War and ignoring slavery altogether strikes one as a less than ideal choice.

But let’s save further discussion of Coppola’s version until it hits theaters.

Siegel’s take is a simple story. McBurney, a Union soldier wounded in battle, is discovered in the woods by a girl and brought back to the Mississippi mansion housing Martha’s school for girls. Instead of handing him over directly to the Confederate soldiers who pass by daily, the women decide to keep him until his wounds heal, so as not to condemn him to death in prison.

At least that’s their stated reason. Unfulfilled lust is what’s simmering beneath it. The first half of the film finds McBurney taking the measure of his captors and seducing each in the way she desires. Martha he takes his time with, seeing a grown woman in need of everything a husband represents: stability, safety, and romance. Edwina (Elizabeth Hartman), the virginal Bible reader, wants a fantasy of true love and a prince to sweep her off her feet. Carol (Jo Ann Harris) just wants a roll in the hay.

So far, what we have here isn’t much more than a ripe southern gothic romance in the form of a male fantasy: trapped among amorous women starved for love. But McBurney’s seductions serve a purpose larger than his lust. Without these women on his side, it’s death or imprisonment. And yet, given that, he’s not quite the genius of seduction we take him for initially. No sooner does he creep up to Carol’s room than he’s discovered by his other would-be lovers. They are unhappy with his deceptions. An unfortunate surgery results.

In case you haven’t seen The Beguiled, I’ll leave out the details. Suffice to say, there’s plenty of blood. Siegel shoots it like a scene in a horror movie with dramatic lighting, eerie angles, and hacksaw shadows on the walls. Have I said too much?

What with these women taking control of their fates in the face of a lustful male, The Beguiled at moments appears to have female empowerment on its mind, but in the end it’s rather the opposite. It’s a movie about a man merely desirous of satisfying his natural manly lusts trapped by and abused by evil, castrating women. The male fear of women is what’s driving it. On the other hand, McBurney isn’t exactly sympathetic. Flashbacks to his less than noble wartime exploits are intercut with his claims of selfless sacrifice, and as for his potential saviors, he just wants to screw them. Then again, on the other other hand, louse though he is, the women are ultimately shown to be monsters, even the adorable little girl who first finds him. This is a kind of horror movie, with McBurney as the poor sucker whose car breaks down in front of a lonely deserted mansion. So to speak. It’s designed to put us on McBurney’s side, whatever his shortcomings.

Eastwood does give one of his better performances in it. Done with the spaghetti westerns that made him famous, the early ’70s saw him stretching. At least as far as Clint ever stretched. In ’70 he made a very odd sort of western, Two Mules for Sister Sara (also directed by Siegel), and in ’71, aside from The Beguiled, he appeared in both Play Misty for Me (which was also his debut as a director) and, again for Siegel, Dirty Harry. It was a busy time for Clint.

Like so many other oddball movies from the past that flew under the radar, The Beguiled has grown in stature. It is, in every way, just not quite like anything else. Not wildly different, but a bit off around every corner. The hero isn’t quite a hero, his oppressors aren’t quite oppressors, it’s neither romance nor horror movie yet is nothing else besides romance and horror, and it doesn’t end the way you expect it to, even though it’d be absurd if it ended any other way. I liked it.