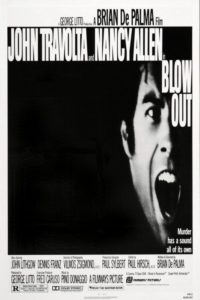

I watched Blow Out (’81) for the first time since the one other time I watched it ages ago, and I wasn’t going to write anything about it, because why bother? It’s just another terrible Brian De Palma flick. Then I began reading articles online about it to find it’s widely seen among the cineratti as a brilliant statement on the nature of film disguised as a scathing, paranoid ‘70s thriller, and without a doubt De Palma’s best film, a work of unqualified genius. I tried to understand what these writers see in the film, but couldn’t. None of the articles get around to explaining why the movie is the work of genius they say it is. They state the genius of the film as unquestioned fact.

I watched Blow Out (’81) for the first time since the one other time I watched it ages ago, and I wasn’t going to write anything about it, because why bother? It’s just another terrible Brian De Palma flick. Then I began reading articles online about it to find it’s widely seen among the cineratti as a brilliant statement on the nature of film disguised as a scathing, paranoid ‘70s thriller, and without a doubt De Palma’s best film, a work of unqualified genius. I tried to understand what these writers see in the film, but couldn’t. None of the articles get around to explaining why the movie is the work of genius they say it is. They state the genius of the film as unquestioned fact.

And so I thought I would question it.

De Palma’s style has never been, to put it mildly, my cup of tea. I grant that he certainly has a style, which puts him in a realm of filmmakers that, like it or not, you have to give some amount of reasoned consideration to. Even though his style borrows with abandon from other filmmakers, you’re never not aware you’re watching a De Palma movie. One is terribly, awfully, outrageously aware one is watching a De Palma movie, every time out.

I find his style to be notable for no other reason than that it’s there, loudly, right up in my face. It doesn’t move me emotionally or artistically. It’s like he glories in making trash, but does it in a way that says “I dare you to call this magnificent art trash!”, thus ruining the fundamental joy of watching actually entertaining trash.

Blow Out is De Palma’s riff on Antonioni’s Blow-Up and Coppola’s The Conversation. Both of his inspirations are subtle, affecting, paranoid statements on what is real and what isn’t, on how the human mind seeks out connections and meaning that aren’t there, or if they are there, are only as there as everything else in the world is there: In the mind of the perceiver.

In Blow-Up, a photographer takes photos of a couple in a park. When he blows up the image, he thinks he sees a man with a gun in the background. He thinks he’s caught a murderer. He even finds a body in the park. But when he looks for it later, it’s gone. What did he really see in his photo? Anything? Or did he lose himself in the pixels of his own feverish imagination? The final scene of a mimed tennis game makes explicit the idea that nothing is real but what we believe.

In The Conversation, a sound-recordist picks up a couple talking. He thinks they’re in trouble. He thinks they’re going to be hurt or killed. But in the end, he fears he’s gotten it all wrong. It’s the couple plotting murder on the tape. Or is it? His tape is stolen. Mysterious forces are listening to him. He tears his apartment to pieces searching for the bug. He can’t find it. He’ll never find it. He’ll never know.

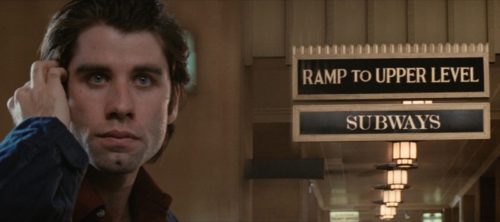

In Blow Out, De Palma tells the straightforward story of a movie soundman, Jack (John Travolta), who, late one night recording atmospheric sounds on a bridge, records a passing car crashing through a guardrail and plunging into the river. He thinks there’s a gunshot on his tape. He thinks a tire of the car was shot out. He thinks the man in the car who died, presidential candidate McRyan, was the victim of assassination.

He’s right. There is nothing ambiguous in Blow Out. The only thing Jack’s wrong about is his assumption that the conspiracy out to get McRyan wanted him dead. They didn’t. They only wanted to catch McRayn with a whore and torpedo his campaign. But the crazy man they hired for the job, Burke (an extra-creepy John Lithgow), takes matters into his own hands and shoots out the tire of the car, and McRyan winds up dead.

The whore in the car, Sally (Nancy Allen), is rescued by Jack before she drowns.

So Burke figures he has to kill her now, to cover up the plot to smear McRyan.

There is nothing ambiguous here, nothing suggesting schemes larger than we perceive operating in the shadows of our lives, controlling out fates. The Parallax View this ain’t.

In terms of plot, it’s just a standard movie-psycho, Burke, killing some people until he’s killed by Jack at the end.

In terms of Blow Out being a meta-commentary on the act of filmmaking itself, I’m equally lost.

On the bridge that very same night is a photographer, Manny (Dennis Franz). Turns out he’s Sally’s boyfriend. They run a business setting up philanderers and taking photos of them. McRyan was just another job. Sally rides in the car with McRyan, Manny takes photos of them. Why he decides to take those photos while the car is moving, in the dark, on a lonely bridge is not answered. De Palma is many things, but logical is not one of them. Which is to his credit or not, depending on your taste.

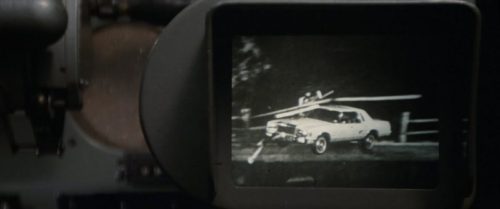

Now we have Jack’s audio, and Manny’s series of photos taken of the car spinning out of control and going over the bridge. Jack puts the photos together as a film, then lays his audio over it.

At which point I was thinking, how does this prove anything? He could lay the audio over it any way he wants, so we hear the alleged gunshot at any point in the car’s journey. Manny didn’t take 24 photos per second. How long Jack lets each photo play and how he lays on the audio is entirely up to him. His little creation proves nothing at all.

Such a set-up is ripe for showing the lies movies tell us. Jack lies to himself about what he heard and devises “proof” which isn’t proof at all, but a story he tells himself to back up his belief. Great!

Only that’s not Blow Out. The gunshot is real. Everything is real. Everything Jack supposes to be true is true. I don’t get where the film commentary comes in here. The film he creates is, in the context of the movie, not at all suspect. It’s the real deal. It’s a genius bit of creative sleuthing proving true what we already know happened.

Jack’s only setback is caused by absurd plot contrivances robbing him of his finished film, and resulting in Sally’s death. Jack holds her dead body while a camera spins around, a massive fireworks display filling the screen behind them. It’s a wild cinematic image. Why it’s there for her death, I don’t know. Big emotions equal big explosions? This sums up De Palma to me: An image that, taken alone, out of context, looks really cool, but that taken in context has no context. This shot mirrors one earlier in the movie when Jack finds all his tapes have been erased. The camera spins slowly in the middle of the room, around and around and around—we could not be made more aware that cinema is happening here—and all I can think is, why? Is this a comment on the artificiality of cinematic tricks? Is that what I should be thinking while watching the scene? How very…technical.

So anyhow, Sally dies while Jack, at a distance, records Burke killing her. He records her death scream. Which scream, at the end of the movie, he hands over to the director of the teen slasher flick he’s working on. Tears in his eyes, he listens to the scream over and over again as they lay it into the movie.

Alas, the irony!

Only wait. Is it irony? No. What is it? A telling commentary on real screams and fake ones? On movie screams being fakery? Unless they’re real screams? In which case they’re real? Or that the movies we watch are fake and so is this one? Because her scream is still fake for us? But it’s real for Jack? Who’s also fake? I find this business so muddled as to be incomprehensible.

Mostly I think De Palma liked the girl being killed.

There’s just no getting around De Palma’s love of killing off young, naked women in his movies. He thrills to it. He gets off on it. It’s not subtle. It is, at the very least, unsettling. At worst, it’s something much worse.

Blow Out opens as though it’s a teen slasher movie. A POV killer stalks scantilly clad co-eds dancing in their dorm rooms, sneaks into the bathroom and makes to stab a naked girl taking a shower. De Palma sure likes terrorizing naked girls in showers. The girl screams—and it’s the most ridiculous scream you’ve ever heard. It’s the “Hulk running” of girls in showers screaming.

Cut to the editing bay, and Jack, and the director, and how he needs to find a better scream. Oh, you will, Jack. You will. Mwa ha ha! So that’s how the movie’s tied together, with the search for a girl screaming as she’s murdered.

Why does Sally have to die at the end? What’s her death got to do with anything? I guess it makes her scream that much worse?

Speaking of Sally’s death, the plot contrivances getting us there are absurd. Jack makes a deal with a newsman who believes Jack’s story of a gun shooting out the tire and the subsequent cover-up. Jack’s going to give him the film to play on the air. But clever Burke phones Sally, claims he’s the newsman, says he wants only her to deliver the evidence, and sets a place for the meet.

Why anyone would believe him is ridiculous. It’s so ridicuous De Palma even has Jack, when Sally tells him about the call, say it’s ridiculous. Why would the newsman call her? Why would he want her to bring the movie? It makes no sense at all. Says Jack, quite reasonably.

Jack therefore makes a single phone call to the newsman to ask him what’s up, they realize the killer has set up a meet and will be waiting there for Sally, call the police, catch Burke, and air the film revealing the plot to smear McRyan.

Oh, wait, no he doesn’t. Instead he says, well, crazy at it sounds, I guess we have to do it. Then he angrily observes how he hasn’t got time to make a copy of his movie. Of all the luck! He gives the lone copy to Sally, wires her for sound, and sends her off to meet the crazed killer. She meets him, he destroys the evidence and kills her.

It’s like the movie is nothing more than a jumble of tropes and references to other movies thrown together without any concern for story or character logic. Which is actually how I’d describe all of De Palma’s movies.

Others would have it otherwise. To them I say: Have at it! De Palma’s all yours.

Loved to read this article, I agree with most of your point about the geniune flaws with the plot of movie but I also don’t worry about most of them as they don’t affect the experience of me watching this. Despite being so cognizant what I couldn’t understand how it is not obvious to you what the ending meant. De palma was mocking the standard formula of american movies in which the protagonist reached his objective(getting the scream) apart from the fact he really doesn’t in the film. This is exactly how you should be ending the film any other way seems to be dated and boring in my opinion. I also enjoyed the fireworks sequence, I thought it worked very well with the melodramatic music playing in the background giving it a finale but a sad one, I think it was more cinematic(unnoticeably) and less cool.

I’m glad I came across this review. I somehow have missed this movie over the course of my lifetime. It came out when I was in high school, but I had never seen it. So I decided to rent it last night after seeing that Roger Ebert gave it four stars, and the other reviews were generally positive. (I generally trust his reviews, but with a grain of salt. How he could give this movie four stars and pan A Clock

work Orange is bewildering).

I was beginning to think it was just me that disagrees with the critics who think this is a great movie. But JHTDC, I could barely make it through. To be charitable, I just want to say that it hasn’t stood the test of time. But deep down, I think even in the 1980s I would’ve thought it was super cheesy.

Glad to have provided a small ray of light in this bleak, DePalma worshiping world of ours. It was definitely as bad today as it was when it came out. As for Ebert, he has some wise things to say now and again, but the grain of salt I take his reviews with is, often, mighty big. The man panned Blue Velvet! Despised The Thing! Thumbs-upped Cop and a Half!

I’m glad that, after some searching, I was able to find a dissenting voice- I agree with almost everything here. However: Manny shoots a film, not a series of photos. At first Jack only has access to photos from the film, as printed in a magazine. From these he reconstructs part of the film, and is able to sync it with his audio. Later he gets access to the original film, on which the gun shot is clearly visible. (I guess we’re meant to believe that Manny has somehow been able to convince reporters his film is real but without showing a clear copy to anyone, only some grainy photos?? It’s all absurd and doesn’t add up at all, any way you slice it.)

Disappointed to hear you were disappointed. The fact that you don’t see the self-reflexivity of the film’s narrative trajectory and especially the climax is surprising to me. This is one of my favorite films and I’m no De Palma fanboy. The personal and political become metaphorically intertwined with Sally’s death and Jack’s failed attempt to save her and the tapes, and the self-reflexivity/metacommentary is laid bare in the final moments.

Neil Bahadur’s insightful take on the film might also help clarify this:

“‘I know what I heard and I saw, and I’m not gonna stop until everyone in this fucking country hears and sees the same thing.'” – Jack

To believe that the above statement, as far as social repetition is concerned, is an anomaly, is probably untrue. But in America at the least, it’s never worked. The moment where De Palma develops into Hollywood’s preeminent political filmmaker, a total cut above his contemporaries, making a film on the seeming impossibility of social change in America, and on the failure of his own generation.

The closing sequences remain some of the best material of De Palma’s career, like the metaphorical charge through the parade – the parade [along with the fireworks] is the cover-up, and to break the illusion is to break everything America is founded on. At the end, everything is a metaphor – even Travolta in the screening room, which only makes sense as De Palma himself, having failed at his own ideals, repackaging trauma and violence into exploitation [what Hollywood and the entertainment industry thrives on and continues to do to this very day; this is the self-reflexive element/metacommentary]. De Palma up to this point was always the most politically interesting of the 70s New Hollywood directors, but he only became a master once he let his films become personal.” – Bahadur

It is maybe my favorite movie about movies; it illuminates the troubling power and magic of cinema (and media at large); its essential purposes as both art and entertainment, and the way those come into conflict–as entertainment, it can serve as a Hollywood smokescreen that manipulates and/or distracts us from the deeper, darker truths of both our sociopolitical landscape and of everyday life, but as art, it can also serve as an audiovisual gateway into the emotional realties of our achingly isolated–and ultimately, tragically human–experiences. In the end, Jack ironically still did his job: he got his scream, but it’s all that was left of her, and ultimately of him too. The ending is as richly sardonic as it is bone-chillingly devastating.

Hope you consider giving it another look sometime.

Thanks for the thoughtful comment. I appreciate the insight into what it is that excites and moves people about this movie. And yet… I’m just not there. For any of this to work, there has to be a movie at its core, one that’s compelling and watchable on its own terms, and that’s where De Palma falls apart for me. That one may read into it all of what you relate is interesting, and maybe that’s enough, but if the simple experience of watching a narrative doesn’t grip me at all, then what may or may not be read into it is beside the point.

Beyond that, I’m not buying Bahadur’s reading. The idea that De Palma is commenting on some failure of his own ideals in this movie strikes me as a reach. Nowhere in his career is it suggested he’s strugging to make anything other than what he’s making. Does he consider his ideals as a filmmaker to have been thwarted by economic and political reality? If so, where are those ideals? In what movie? Or did he fail before he ever began?

I note in my essay that a problem I have with De Palma is that he gussies up his trash to seem important, at which I find he fails, and which at the same time ruins the simple joys of trashy movies. So Bahadur going on about Hollywood repackaging trauma as exploitation etc., the problem here is that this suggests any form of action/horror/trash cinema is “exploitive,” which is it? Can’t movies be fun? Even if they’re violent? Isn’t there value to be had in experiencing on film what would be awful, traumatic events in real life? Isn’t this a major function of storytelling? To allow us to imagine horrors we’d in real life never want to have to endure?

I feel like with this analysis De Palma is just being dropped into that irritating world of filmmakers who make some over-the-top violent flick the point of which is to comment negatively on the the public’s love of watching over-the-top violent flicks (Natural Born Killers, Man Bites Dog, Funny Games, etc.). It feels both defensive and arrogant on the part of the filmmakers to provide in their movies exactly and only the pleasures they’re simultaneously telling us we’re wrong to enjoy.

The ending of the film doesn’t communicate to me what it does to you, and this may be because I find the narrative so uncompelling. I don’t feel any emotional investment with Jack, and thus his woes don’t translate into an appreciation for some particular interpretation of what is art and what is entertainment.

Maybe some day I’ll watch it again, but it’s pretty far down the list at present…