When Big Time opened in 1988, it didn’t. Not by much, anyhow. It played briefly in New York and L.A., and, as far as I can tell, nowhere else, aside from rep houses as the years passed.

When Big Time opened in 1988, it didn’t. Not by much, anyhow. It played briefly in New York and L.A., and, as far as I can tell, nowhere else, aside from rep houses as the years passed.

Critics panned it. The reviews are simple and may be paraphrased thus: “The filmmakers did it wrong. They should have just filmed a Tom Waits concert and let us watch it.”

No finer examples of critics unwilling to engage with a film’s aesthetic could be found.

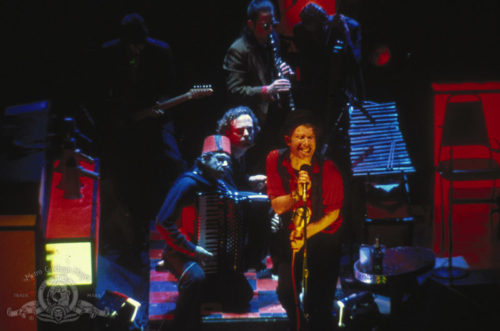

Yes, Waits and director Chris Blum and editor Glen Scantlebury could have eased up on the whole “movie” concept and shot Waits’s elaborate stage show as is. I am sure we all would have enjoyed it. It is, after all, Tom Waits, performing songs from his three (then) most recent albums, Frank’s Wild Years, Rain Dogs, and Swordfishtrombones. His band, including spiky guitar genius Marc Ribot and all-around bizarre horn-man Ralph Carney (whose nephew, by the by, is Patrick Carney, the drumming half of the Black Keys), is simultaneously as tight as a bucket of crab apples and as loose as a busted table saw. A straight-up filmed concert would have been jim dandy indeed.

Also, it would have been nothing but a straight-up concert film. Jonathan Demme took that form to its extreme in ’84 with Talking Heads and Stop Making Sense by turning a concert into a story, irrespective of lyrics, and doing it without ever leaving the stage.

Waits and Blum took a different route. There’s a kind of story being told in Big Time, an abstract one, one whose only characters are those played by Waits, in scenes theatrically designed to resemble the stage-show it’s intercut with. Waits is a ticket-taker at a movie-house, a man tossing playing cards into a hat in a bathroom, a sleazy watch salesman, and a man asleep in bed who wakes up to find all of these people and more crackling to life on his TV set. He is Frank, living his wild years.

These versions of Frank don’t really do anything but exist as images from Frank’s life, the life Waits is singing about on stage. The effect is, in a word, weird. The editing is fast and jarring. Tom Waits singing on stage is intercut with Tom Waits lip-synching in a faux-alley. Marc Ribot goes bonkers in “Telephone Call from Istanbul” and we’re hanging out with Waits in a bathroom. Waits recites “9th and Hennepin” under an umbrella on fire.

One could complain about such a movie. Or, one could take its hand and let it lead you where it wants to go.

This is what I did, and lemme tell, it was a pleasure. As much as I’d like to see a full Tom Waits concert from this era, in the world of movies what I most like to see is that which I haven’t seen before. I have not seen a concert film like Big Time before. Or since, for that matter. It’s a unique piece of work featuring a non-stop string of brilliant songs. That the movie was so dumped upon when released just goes to show how out of step Waits was with the times.

The ‘80s were fucked up, musically, especially for artists who’d made their name in the ‘60s or ‘70s. No matter who you were, if you made it to the ‘80s as a recording artist, your music sounded like the ‘80s. Those drums! Those synths! You might have made great music (Peter Gabriel!), or you might have made the worst music known to humankind (Starship!), but if you made music and you made it in the ‘80s, the ’80s is what it sounded like.

Unless you were Tom Waits.

In ’83 he put out Swordfishtrombones. It sounds like it was recorded in the 247360s (or so) in a junkyard on the moon under a sky raining rusty kazoos. It’s almost nothing like his previous records, and is so at odds with everything else of its era it’s hard to believe Waits didn’t discover the tracks hidden in a broken down time machine and lay his vocals over them recorded through a microphone stuffed in a bucket of wet sand.

Few musicians have ever managed to reinvent themselves the way Waits did with Swordfishtrombones. Rain Dogs and Frank’s Wild Years continued in a similar yet ever-evolving vein, eventually leading up his new style’s apotheosis in Bone Machine, which I’m pretty sure he recorded in the 1920s on the set of Metropolis.

So, Big Time, 1988. The late ‘80s in full, horrific swing, hair bands on every corner, a truly ghastly era in music, and Waits arrives with this crazy-ass, unique concert film featuring crooked, slinky, merry-go-round show tunes no one but the weirdest hipsters would be into anyway, but who didn’t get the chance because the critics didn’t approve and the movie vanished, almost totally unseen.

If you love Waits—and who doesn’t love Waits?—you will love this movie. It’s impossible not to. It’s song after brilliant song, played by one of his very best bands.

It ends with “Innocent When You Dream.” Waits sings it standing in a bathtub on stage. No cutaways with this tune. It’s a dreamy, crackling waltz, and as soon as it began I knew it was the last song. That’s how effective this movie is: When it arrives at the goddamn waltz, you know it’s the show closer. It’s a riveting performance (and, because who the fuck knows why, it does not appear on the movie’s soundtrack).

A rocker plays under the credits, and that’s that. I wish you could see it, but it’s going to be tricky. Big Time exists on VHS. That’s it, home-viewing-wise. If you live in the San Francisco Bay Area, you’re in luck. A lovely 35mm print (the director’s own, in fact) is showing at the Roxie in S.F. on November 1st. It’s worth the effort to see it. I caught one of two previous shows earlier this month (thanks to Jesse Hawthorne Ficks of Midnites For Maniacs, who played it on a double bill with Down by Law). You really oughtta check it out. Who knows when the chance might come again.

Well I will see it so there! If anyone wants to join me, I’ll be at the Roxie on 11/1.

I saw the encore screening at the Roxie. It was just ok. Of course TW fanboys were flipping out.

I have it on Japanese LaserDisc and it’s a cool and weird in-sync performance, expect the unexpected. Pure Waits, IMHO. Since September 1, 2023 has now seen the digital remaster of Tom’s mid-career trilogy (overseen by Tom, Kathleen and Tom’s audio engineer) on CD and Vinyl, Amazon shouldn’t just sell these but put Big Time back in its streaming program (which they first did September 2020).