Turn on your television these days and you will find a strong uniformity to the editing on many of the shows that fall into the “non-scripted” category. Explanatory voiceover drawn from character interviews is ubiquitous (to explain in words what is already being shown in pictures), music is omni-present (to dictate how the audience should feel), and the cutting is quick and assertive (to keep the stimulation level high). Whether it’s reality TV shows, HGTV fix-it shows, true crime fare, or almost anything else, the information delivery strategy is surprisingly consistent across genres. Call it “sugar rush cutting.”

Turn on your television these days and you will find a strong uniformity to the editing on many of the shows that fall into the “non-scripted” category. Explanatory voiceover drawn from character interviews is ubiquitous (to explain in words what is already being shown in pictures), music is omni-present (to dictate how the audience should feel), and the cutting is quick and assertive (to keep the stimulation level high). Whether it’s reality TV shows, HGTV fix-it shows, true crime fare, or almost anything else, the information delivery strategy is surprisingly consistent across genres. Call it “sugar rush cutting.”

The editors of these shows are not robots, and they regularly perform delicate acts of story sculpting within the confines of this style. But it’s clear that they have internalized the perceived demands of the environment in which their shows are consumed. Potential for audience distraction lurks around every corner on television, whether it be the temptation to click to another channel, check a social feed, or leave the room to take a bathroom break. In response, editors must do everything possible to make their confections shout louder and move faster than the distractions that they’re competing with. Stuffed into 5-8 minute segments that are themselves squeezed into rigid 30- or 60- minute blocks, the content must produce continuous short-term satisfaction and deliver our eyeballs to the advertisers paying the bills in the next commercial break.

One alternative to television is, of course, Netflix. The ultimate customers on Netflix are the subscribers, not the advertisers, so there are never any commercial interruptions. Programs can stretch out to luxuriate in unique, odd-sized lengths like 42:43 and 1:18:11. And while some of the audience is undoubtedly still watching in high distraction zones, portions of it will be attempting to simulate the theatre experience by strapping in tight with headphones on a laptop somewhere, or going high-end in the plush confines of a home theatre now that more and more shows are being delivered in 4K.

What, then, do the creators of documentaries commissioned by Netflix do with their rights to self-determination? Free to play in the pastures of limitless time with an audience that is theoretically less fickle, how do their films choose to speak?

Donald Trump in “The Confidence Man”

There is a moment in The Confidence Man, the Donald Trump doc that serves as the concluding episode of Netflix’s Dirty Money series, that shows just how hard it can be to break the adrenaline habit. The film positions itself as a takedown of the “success” narrative that Trump sold himself on to the American public in the 2016 presidential election, and leads its audience through a series of set pieces showing Trump’s business acumen to be less than stellar. By 30 minutes into the 77-minute episode we have arrived at a fallow period in Trump’s career in the mid-’80s, and find him confronted in his office by David Letterman via a Late Show segment from 1986.

“You didn’t know we were coming, we came on up,” says Letterman brightly, a little taken aback at how easy it was to saunter into the offices of The Donald. “How busy can you be?”

“Do you want to know the truth?” Trump responds sheepishly. “I wish I had more to do.”

The moment is meant to underscore the eerie feeling of silence in an otherwise loud career, yet the effect is muted by the relentless pace of the cutting. While the words are telling us that Trump is spending Friday afternoon sitting idle in his office, the aggressive, fast-paced images say something different: Trump’s world is a compelling, lively one.

Another segment of the film ably demonstrates Trump’s addiction to cheap publicity thrills, but again muddies its message with quick cutting. While the parade of archival clips from silly promotions gets the job done of showing him as a two-bit huckster (including a particularly painful one of Trump grinning like an idiot next to Grimace in a McDonalds ad), the cutting silently makes a different point: Trump must be successful because he is everywhere. The look-and-feel of The Confidence Man is one that Trump himself would fit right in with: assertive, emphatic, eager to please. Using this style of cutting with Trump is like trying to fight the firehose-strength stream of nonsense coming out of his mouth with just another firehose.

It is surely unfair to ask this doc to take on the form of a meditative art house drama. As an editor myself, I know that there are a million different reasons why something might end up being cut like this. The sheer amount of material that had to be packed into the show might have made shorthand solutions necessary, even with the luxury of an open-ended running time. The branding of this particular series probably dictated a need to compete on the same terrain as quick-burn shows on television proper. Or the reality of shortened attention spans of audiences everywhere (TV, cable, streaming, and theatrical) may have made the point moot: slow down too much, and you may lose them.

Nonetheless, it’s interesting to contemplate what a different strategy for these scenes might have looked like. I thought of Feed, the 1996 doc directed by Kevin Rafferty and James Ridgeway, which consists entirely of satellite feed footage of politicians and newscasters puffing themselves up just before their interviews go live. The takes are long and painful, with the subjects given plenty of rope with which to hang themselves. The film takes some patience to watch, but that patience is rewarded, and the subjects are not only brought down to size but also ultimately humanized in a way that deepens the complexity of the entire endeavor. If complexity is indeed the goal, one has to be willing to build with high-quality proteins as well as simple sugars.

Errol Morris’ “Wormwood” clocks in at a rotund 258 minutes

We need look no further Errol Morris’ series Wormwood for an example of this on Netflix. It centers on Eric Olson, a 74 year-old man who has spent most of his adult life trying to solve the mystery of his father’s death, and clocks in at a rotund 258 minutes. There is no real logic behind the division points separating the six episodes beyond slicing the whole into semi-equal parts, so I think it’s fair to look at the work as one feature instead of six featurettes. As such, it has been accused of suffering from the opposite affliction of The Confidence Man: the dreaded “Netflix bloat.”

Yet in the face of the unrelenting noise of ordinary TV cutting, I found myself reveling in the bloat. Two characters exit a house and we see their complete egress, their figures slowly diminishing in size as we view them through a small window in the front door. Someone walks down a long, bleak hallway and we see every one of their steps as the shot drags on for 20 or even 30 seconds. This slack pace wouldn’t work if the underlying story were not so compelling, but a compelling story it is. And the pauses between narrative beats give time for the atmosphere to suffice our thoughts, and for the information in the latest segment to play out in our own imaginations.

Such a pace also allows for the editor to take charge of the dynamics to sculpt the film’s meaning. Having established that long moments of repose are part of the mix, the segments that move faster actually feel fast, which in turn gives stronger meaning to even the shorter pauses. Nowhere is this more beautifully demonstrated than in the last scene of the film:

Olson sits in the interview chair and poses a series of rhetorical questions. “You think that finding the answer to this is going to restore the path of your own life,” he says, reflecting on the ultimate folly of his project. “But how can it possibly do that if you’ve lost yourself along the way?” Each of his subsequent lines is shown from a different camera angle, the rhythm getting more and more insistent with each cut.

“Do you think you’re going to get a judicial decision? Do you think somebody is eventually going to pay the bills for all this?” Cut.

“Do you think you’re going to find peace of mind?” Cut.

“What’s that going to consist of?” Cut.

“You’re going to find out that [content removed to avoid spoilers].” Cut.

“Do you feel better now?” Cut.

“Do you feel better now?” Cut.

“Is that better than not knowing? Is it?”

The editing has created a quickening pulse, which is finally relaxed as he comes to a close. “Wormwood,” he says, referencing a passage in Revelation that he quoted at the beginning of the film. “It’s all bitter.”

What follows is an amazing 10-second post-quote pause as we watch Olson’s face cascade from dark amusement to a flash of barely concealed rage to a final movement of the jaw that seems to ask the audience to share in his trauma, before the film ends with a dramatic cut to the end credits. The moment is riveting.

Why is it so powerful? Not only because of the raw power of the emotions that read on Olson’s face, but also because it is played in one continuous shot. Editor Steven Hathaway is using the power of dynamics to create a kinesthetic complement to the verbal/intellectual message. The shot durations decrease from a relatively languid 7 seconds at the outset to a taut 2 seconds with “Is it?”, which makes the 10-second non-verbal pause at the end feel like an eternity, and focuses the audience’s attention on the most minute details in the emotions that read on his face. The silence is deafening.

Interestingly, Wormwood is entirely consistent with sugar rush cutting when it comes to music. The soundtrack swirls and flows like it’s part of the scenery, and never lets up. To truly find an alternative to this kind of editing you may have to leave Netflix entirely, which is itself an ecosystem of instantly clickable distraction, and go to the land of the independent, grant-funded documentary.

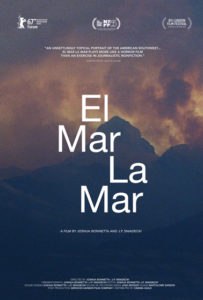

An exercise in patience

Currently showing in a limited theatrical release, Joshua Bonnetta and JP Sniadecki’s El Mar La Mar is an immersive journey through the Sonoran Desert shot along the U.S. / Mexico border. The entire film is an exercise in patient mood-building, with shots that play out for two or three minutes apiece, and sound sculptures that ebb and flow in breathtakingly beautiful ways. One section plays out on an entirely black screen, the only thing visible the subtitles to a long soliloquy delivered in Spanish, focusing your attention on the gorgeous texture of the voice. If Feed requires patience, this film is the embodiment of it, not for its own sake but for the sake of an exquisite imaginary world created on film.

Perhaps, in identifying “sugar rush cutting,” it is patience–and the lack thereof–that is really the bottom line. Does the content in question ever stop to lower our pulse once it’s been raised? Do we get to learn and feel and explore? Are we ever truly surprised? When you are watching your next documentary, ask yourself whether you were ever asked for patience, and if so, whether it was rewarded.