In 1975, actor Leon Vitali, after having appeared primarily in British TV shows, found himself cast in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon as Lord Bullingdon. For an actor in 1975, landing a prominent role in a Kubrick film was a major step to stardom. For Vitali, it led somewhere far more interesting than acting fame.

Vitali and Kubrick hit it off on the set of Barry Lyndon. Kubrick liked Vitali’s work so much that he wrote him into more scenes than originally planned. Vitali was thrilled. But even more thrilling, and, to him, having worked only in television and on a couple of small films, fascinating, was witnessing the scope of Kubrick’s production. The number of people involved. The number of artists, of technicians, all answering to Kubrick, all devoted to bringing Kubrick’s vision to life. This, thought Vitali, is what I want to do.

He told Kubrick that he wanted to work for him behind the scenes on future films. Kubrick told him to study up and get back to him. So, on Vitali’s next film—he was offered many roles following Barry Lyndon’s release—he asked if he could hang out in the editing room, unpaid, and learn how the final product was put together.

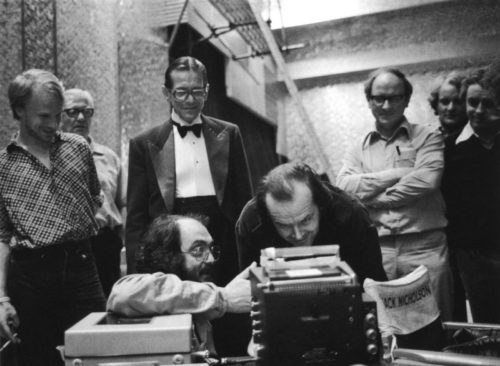

Eventually Vitali wrote Kubrick detailing what he’d been studying. Kubrick responded by sending Vitali a book: The Shining. Read it, said Kubrick. When he had, Kubrick asked him what he thought. Vitali thought it would make a great movie. So Kubrick told him to fly to America and find a child actor to play Danny Torrance.

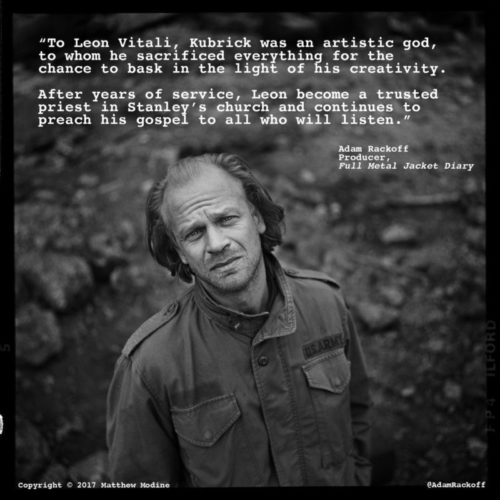

And thus, Vitali became Kubrick’s right-hand man until and beyond Kubrick’s death.

Filmworker—the job description Vitali gave himself—details Vitali’s working relationship with Kubrick on The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and Eyes Wide Shut, and it’s a lovely story about the love of movies and the power of genuis. It’s directed by Tony Zierra, who stumbled onto Vitali’s story while working on another Kubrick-related documentary, and decided Vitali merited a movie of his own.

Kubrick had a passion for details, as is well known. He was a perfectionist. An extreme one. He was of the opinion, reasonable from his perspective, that no one else cared as much as he did. When someone did, in fact, provide a high level of artistic work for him, his opinion didn’t change—however much someone did, they could always do more. So, doing one’s best for Kubrick only meant you’d now have to do better.

In Vitali’s case, this meant that, once Kubrick came to trust him, he relied on Vitali for everything and anything. Vitali typically worked 14 hour days for Kubrick. And that was just on set or at Kubrick’s house. Back home, Vitali kept right on working. Being a trusted creative confidante of Kubrick’s was to give up your life for his.

Another recent film, S is for Stanley (2015), tells a similar story, about Kubrick’s loyal chauffeur and assistant, Emilio D’Alessandro. But in that film, Kubrick remains in the background. It is instead the story of a very charming Italian immigrant unstudied in the ways of cinema who stumbled into 30 years of service to a master filmmaker. There’s little about Kubrick’s movies in it. What one does come to learn, however, is that once Kubrick takes you in, you’re his, for life.

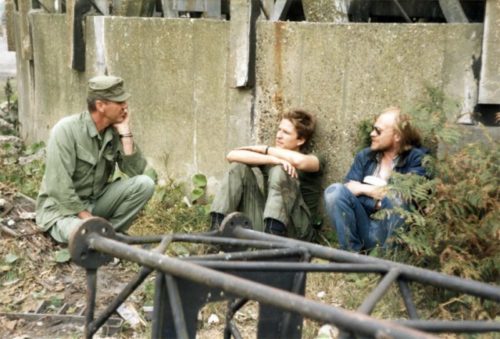

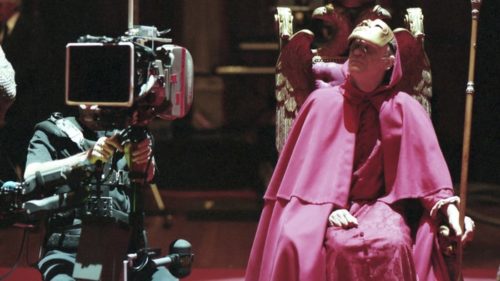

Because Filmworker goes deep into the making of Kubrick’s last three movies, because Vitali was right there on set, doing everything from coaching actors to overseeing prints to cutting trailers for every country in the world, it’s a much more compelling film.

Vitali is interviewed extensively. He’s a delightful character. Other interviewees include Ryan O’Neal, Matthew Modine, R. Lee Ermey, Stellan Skarsgård, and Danny Lloyd (all grown up! I don’t think I’ve ever seen him interviewed before), plus various other film industry folks.

The thrust of many of these people’s comments is to wonder at Vitali having “given up” a promising acting career to be Kubrick’s assistant. Of course form Vitali’s perspective, he didn’t give up a thing. I find I side with Vitali on the matter. Is acting in movies really the best one can hope for in life? At least Modine is straight up honest about it, admitting he’s “too selfish” to do what Vitali did.

What Vitali did was become an invaluable (and unrecognized! I never knew!) aid to one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. Sure, if he hadn’t, he could have starred in a series of TV shows and movies made by, primarily, directors far less accomplished than Kubrick. Who knows, maybe he would have won an award or two. Yawn.

Instead, he’s the guy who discovered Danny and the twins for The Shining, who first caught on to R. Lee Ermey being the man for Full Metal Jacket, and who, to this day, because of his years of work ensuring that Kubrick’s negatives and prints were exactly as Kubrick wanted them, oversees all (or most, or many) releases of Kubrick’s films on whatever media they’re being released. Instead, he learned to see through the eyes of a master artist, to understand film as he did, to seek the kind of perfection he sought.

For a lot of people, certainly for a lot of artists, that might feel like forgoing your own life to live another’s. For Vitali, it appears no other life would have been half as fulfilling.

Filmworker is packed with clips and photos from Kubrick’s productions, and it’s full of fascinating stories, such as R. Lee Ermey’s about how it was Vitali who was responsible for his replacing the actor originally hired to play Sgt. Hartman (which actor, who would play the helicopter machine-gunner in one memorable scene, is on hand to recount the trauma of losing a starring role in a Kubrick film eight months after being hired). As you would expect, Ermey is hilarious.

The one odd thing about Filmworker is something I notice creeping into other documentaries these days. Every now and then they switch to animation of Vitali and Kubrick, in this case purposefully simplistic and, well, bad animation, for no apparent reason or purpose other than, I find, to distract and annoy. With their wealth of photos and footage, why not show us something interesting?

But whatever. Irritating animations aside, Filmworker is a lovely tribute both to Kubrick and to Vitali. If you’re into Kubrick’s movies—and you’re here, reading Stand By For Mind Control, so of course you are—you need to check this one out.

Filmworker opens June 8 in the San Francisco Bay Area (where SBFMC Laboratories are located) and, I reckon, in other places too, sooner or later. So get on it, people!