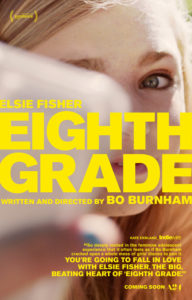

Acne, acute embarrassment, blow-job bananas, creepy dudes, chummy dads, hideous popular girls, and etc. feature in writer/director Bo Burnham’s debut movie, Eighth Grade, starring Elsie Fisher as believably awkward and bepimpled Kayla Day, soon to finish her eighth grade year and move on to the big, bad world of high school.

It’s not bad. Many scenes are just right, my favorite involving Kayla, her dad (Josh Hamilton), and a banana. Other scenes feel more like they’re skating along the surface of real life without ever going deeper. Perhaps prime among these are the many scenes of Kayla making YouTube videos of herself as she ponders life, the universe, and everything. Which, sure, kids do such things. But Kalya’s videos are much too perfectly imperfect and, like, you know, real.

Which led me, by movie’s end, to thinking about the style of realism, which Eighth Grade doubles down on. And the thing about realism in movies is this: it’s as much a stylization of the real world as is any other style. This is necessarily so, because it is not real life we’re watching. We are watching a movie. Every movie is stylized, be it fiction or documentary. Realism, as a style, is no different, no better or worse, than any other style, and like any other style, if it calls too much attention to itself, the style becomes the focal point rather than the content it’s stylizing.

For the style that is realism, this results in something counterintuitive: the more you heighten the realism, the less real becomes your movie. Just as the stylization of, say, a Joel Schumacher movie results in less realism. In fact, to achieve the feeling of realism, there’s no reason to use a so-called “realistic” style. If you want to really feel what it’s like to be a salesman, you watch Glengarry Glen Ross (or you go full documentary, and watch Salesman). But you wouldn’t call anything Mamet writes “real.” Nobody actually talks like Mamet’s characters talk. He uses his heightened stylism to find truth.

The same is true of any artist with a distinct style. Robert Altman’s style falls into something like realism, with his controlled chaos and overlapping dialogue, but MASH, though it makes us feel we’re witnessing what war is really like, could hardly be called an accurate depiction of reality. It’s a style, one that, used as brilliantly as Altman uses it, shows us something truthful.

And thus I am reminded, as I so often am, of Werner Herzog’s definitions of ecstatic truth and the accountant’s truth. The accountant’s truth, the purview of Cinéma Vérité, is a superficial truth, simply filming what is there, and calling it honest. Whereas, per Herzog, “there are deeper strata of truth in cinema, and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.”

Any style may be used to get at poetic truth. Realism might feel intuitively like the best way to get to the truth of reality. It’s right there in its name! And indeed, it may be used well. But defaulting to realism, i.e. consciously intending to remove stylization such that only the truth remains, is to misunderstand poetic truth, it is to assume your lack of obvious affect will do the heavy lifting for you. It might, with regards the accountant’s truth, but to achieve something deeper requires harder work.

By the end of Eighth Grade, these were the thoughts I was thinking. It’s a movie that proudly asserts its honest realism while ultimately feeling very much like a movie, a tiny slice-of-life movie about a girl facing the issues all kids in movies like this face, in pretty much the same way they always face them. The popular kids are mean cliches with zero depth or character beyond being popular and mean, dad is a standard nice guy goofball, who, at his daughter’s saddest moment, gives her a casual, halting speech of love and beauty so guileless and unrehearsed it couldn’t feel more written for the movies, and our hero even tells off the mean girls at the end. Eighth Grade hits these beats well enough. It’s a likeable movie. It just presents itself as something it isn’t: real. It’s not real. It’s a movie. A movie you have, in large part, seen before.

Well said. I wonder what you thought of the “realism” in Short Term 12. I remember that film being piercingly emotional, and very, uh, real.

I haven’t seen it. But I recall Mr. Evil Genius writing about it and saying I should. Nothing wrong with realism as a style, of course. I’m sure we could name plenty of movies that do it well. But it’s a style that lends itself to laziness and, at times, to pretentiousness, rather easily. And it’s important to remember that it IS a style–rather than the absence of one.

Yeah. It’s been a while but I found Short Term 12 very powerful. Probably worth a re-watch now that Lakeith Stanfield has become such a well-recognized name.