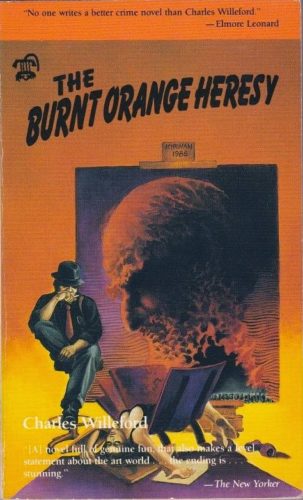

Charles Willeford wrote crime novels set mostly in the south, mostly in Florida, about criminals, psychopaths, or just regular people (where to Willeford “regular people” might well be criminals and/or psychopaths). His style is simple and straightforward, with great attention to detail, and his plots unfold slowly, almost casually, without emphasis, without melodrama or theatrics, before more often than not ending with something horrible happening. (And he’s funny, too. As he put it, “Just tell the truth, and they’ll accuse you of writing black humor.”) He’s the kind of writer who seems almost not to be doing much, writing-wise, until you realize he is. Other crime writers venerate him. Few match him.

The Burnt Orange Heresy, from ’71, is arguably his best. It’s something like a noir, but it’s something else too. Set in the Florida art scene, it’s a story about up-and-coming art critic James Figueras, a man fiercely dedicated to the importance of criticism in providing a link between artist and audience, who believes he could become the most respected modern art critic in America.

Willeford spends much of this short novel expounding philosophically and hilariously on the nature of 20th century art, of art criticism, of the value of art, and of artists themselves. It amounts to a scathing critique. What’s more impressive is how the noir plot takes to its logical extreme Figueras’s belief that critics are necessary, as necessary as the artists themselves. For a crime novel, it couldn’t be more unusual.

And now there’s a film version.

Improbably, Willeford, unlike most novelists, has been well-served by filmdom. Monte Hellman made Cockfighter in ’74, with Warren Oates and Harry Dean Stanton. It’s a low-key slow-burn, but so is the novel. In ’90 George Armitage made one of the great ‘80s neo-noirs with Miami Blues, the first of Willeford’s series about low-rent Miami cop Hoke Moseley. And best of all, in ’99 Robinson Devor adapted The Woman Chaser, Willeford’s other best novel, turning it into one of the oddest and most transporting comic-but-deadly-serious modern noirs ever made (which I wrote about at length here).

It was a streak that couldn’t last.

The Burnt Orange Heresy, directed by Giuseppe Capotondi and written by Scott Smith, is, judged on its own merits, dull and thematically muddled. Judged as an adaptation, it’s appalling.

Adaptations that slavishly adhere to their source material inevitably make poor movies. Being “true to the book” is always a mistake. What’s important is finding the core of what makes a book worth adapting, and then presenting that core cinematically. Mess with the story, the characters, the order of scenes, whatever you want, whatever it takes to bring a story from one medium into another without losing the story. This is the point of adaptation. But if you’re simply going to toss out the source material, why use it in the first place?

The Burnt Orange Heresy dispenses with everything of Willeford’s —the humor, the characters, the locale, the theme, the point—save the basic plot elements. Given the relative obscurity of the book, one has to wonder why they even bothered with it. Why not just write an original movie?

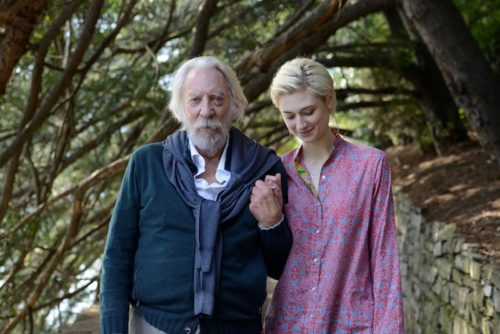

The movie is set not in the American south of ’71, in seedy motels and tacky art galleries, on the road and in run-down shacks off the highway. It’s set in present day Italy. The action goes down almost entirely at a billionaire’s country estate. James Figueras (Claes Bang) is not a man (pathologically) dedicated to the pure necessity of art criticism. He’s a cynical liar. His new girlfriend, Berenice Hollis (Elizabeth Debicki), is not the plump and somewhat dim school teacher from the novel, but an anorexically thin, hard-nosed teacher on a European vacation, there to escape her recent shaming as an adulteress. And the mysterious, rarely-interviewed artist at the center of the story is no longer the enigmatic oddball drawn by Willeford, but a generic, platitude-spouting, wise old gentleman played by Donald Sutherland.

Every alteration weakens the story. What began as a strange and unique take-down of art, artists, and critics has become a blandly generic, shiny lump of Euro-trash it’s hard to believe wasn’t made in the ‘90s. Everyone just sits around smoking, looking beautiful, and trying to out-bon mot one another while conspicuously hiding their pasts.

Most confusing is why screenwriter Smith gutted the very point of the novel. In the novel, key to everything is the slowly dawning possibility that world famous artist Jacques Debierue has never painted anything in his life, that his only work, the one that made him famous in ‘20s Paris, was an empty frame he hung on a cracked plaster wall. In the book, there are no photos of Debierue paintings, he’s granted almost no interviews, and what few he has contain the only descriptions of otherwise unseen Debierue artworks. Willeford has it in for Dadaists and Surrealists, and Debierue, the supposed missing link between these schools, embodies their worst traits.

In the film, famous artist Jerome Debney has likewise not painted anything lately, but the basis of his fame is never discussed. Past fires have destroyed his life’s work, but the existence of that work is never questioned. Indeed, his earned status as a famous painter is never questioned. That his paintings have been seen the world over is assumed. The film is concerned only with the vague and corny notion that Debney’s work has weighed down his soul, you see, and thus its recent loss in a fire has freed him. He doesn’t see why sharing his art with the world matters; what matters is what’s inside him. Brings a damn tear to one’s eye.

Debney is exactly who he appears to be. So is Figueras. We come to know him as a liar who once went so far as to write a famed critique of a piece he knew was a forgery. When the movie culminates with Figueras’s criminal act, it’s neither surprising nor reveletory. As written by Willeford, Figueras, the novel’s narrator, is smart, well-spoken, and sure of himself. Very sure of himself. Only as the book progresses do we begin to realize that Figueras, like so many Willeford characters, like so many actual people, is delusional. And only at the end do we see what that kind of self-delusion can lead to.

The movie ends with a crime, of course. A few crimes, even. While these supply a needed goose to an otherwise dull film, their inclusion tosses out anything like logic. The characters are too simplistic to warrant any real shock by what happens. This sort of thing happens in movies, is all. No matter if this particular movie has earned it.

Even the name of what comes to be the lone painting in question, The Burnt Orange Heresy, is stripped of meaning in the film. In the book, Figueras invents it. He invents a “period” of Debierue’s to which it belongs. He invents more too, but I can’t give everything away. This is all terribly important thematically. In the movie, Debney gives jokey names to all of his blank, unpainted canvasses so that one day critics will be confused. The Burnt Orange Heresy is one of many. Ha ha? I guess? It’s the one Figueras steals because it’s the name of the movie he’s in.

Did I mention Mick Jagger? He plays the billionaire art collector. He’s just fine. We could ask no more of Mick Jagger the film actor. The other performers are fine as well, given what they have to work with. Why give them so little? With so much depth in the source material, why throw it all out? The Burnt Orange Heresy is The Burnt Orange Heresy in name only.

Well then. Can I borrow the book?

Having just read the book, after seeing the film, I totally agree with pretty well everything this critic says. The book is brilliant, and really doesn’t share much more with the film than its title. But I’m grateful to this glossy, confusing movie because it led me to discover Charles Willeford!