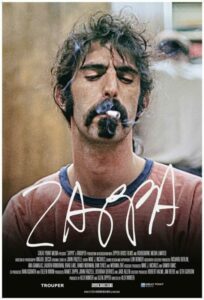

Seems like only yesterday I was writing about Frank Zappa documentaries, and therein noting another one then just funded to be made by most excellent dude Alex Winter. A mere four years and one global pandemic later, it has arrived, with a title freakishly short in the world of modern documentaries: Zappa. This as opposed to what we would expect: Frank Zappa, The Story of a Reluctant Rock-God and One of the Twentieth Century’s Grumpiest and Most Under-Appreciated Composers, which had it been funded by a studio they would have insisted it be called, lest we have any doubt what we were watching and why.

Winter, notably, was given access to the fabled Zappa vaults, wherein his compositions, his recordings both audio and visual, his home movies, and probably at least one bicycle wheel are stored. Winter briefly tours us through the place, leading one to realize no one presently alive on this Earth will ever be around to hear it all no matter how fast they release more unreleased albums and concerts and etc.

Gail Zappa, Frank’s wife, who died in 2015, is interviewed for the film, and doesn’t mince words, mostly about the forces lined up against Zappa during his too-brief life (he died of cancer at age 52). She only agreed to let Winter make the movie, and grant him access to the vault, because she liked Winter’s angle on Zappa. Winter wasn’t interested in making a typical music doc following the artist from album to album, but rather in examining what it meant to be an artist at that time, culturally and politically, what it took for Zappa to make the kind of art the way he made it in the face of those who preferred he didn’t.

In that, Winter succeeds. There’s scant mention of albums, and barely a word about Zappa’s skill as a guitar player. If you’re going for a deep dive into his music, you’ll be disappointed. Instead the movie concerns itself with Zappa the artist, specifically the composer. The movie opens and closes with Zappa, near the end of his life, going to Prague just after the Velvet Revolution. He’d over the years become a hero to many Czechs, a figure of freedom, and when invited to speak and play for them, he gratefully accepted.

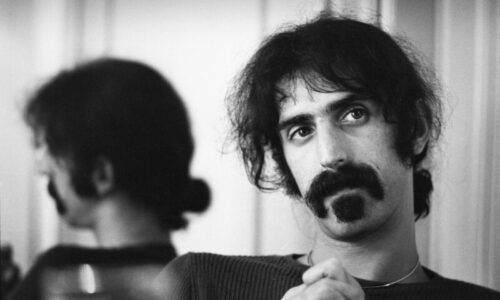

What Winter’s movie makes abundantly clear is that Zappa evoked passion among those who knew him; they loved and hated him in equal measure. Zappa exasperated and drove insane everyone who worked with him—and yet they’re eternally grateful for the experience. Zappa made music like nobody else, like a Martian, like a lunatic, like a very serious musical genius in love with cheap gags. Watching an impassioned Ruth Underwood, Zappa’s brilliant percussionist, may be the film’s greatest pleasure. Zappa’s music, she says, felt written just for her. When she heard it, she knew she had to play it, knew she’d never want to play anything else. Yet for all their years working together, Zappa treated her like every other musician, every other employee, who worked for him. Exasperating, but she loved him just the same. So did everyone who worked with him, or at any rate those interviewed for the movie. According to Winter, all the interviews started the same way. The interviewee would sit down and, unprompted, rant about what an insane bastard Zappa was for a half hour before, finally unwinding, their eyes would grow misty as they spoke of their reverence for the music they made and the time they spent with him.

Steve Vai talks of something said often about Zappa, that he always seemed to know what a musician was capable of, whether they did or not, and would write music specifically to push them to their outer limits.

It was no picnic working for him. He was a perfectionist. It was his strength and his weakness. He pushed and pushed and yet never felt satisfied with the results. There were sounds in his head, and humans just couldn’t seem to recreate them. In the ‘80s he started using a newfangled synthesizer to record his compositions “perfectly,” no pesky humans needed. These are among his least interesting albums (sez me; so there).

What’s most intriguing about Winter’s doc is how it gets at the heart of Zappa. In a way I haven’t seen before, it brings to life the darker side of his genius, how deeply he frustrated everyone who interacted with him, from his musicians to his children, or the way this very funny man could at times be so bloody humorless. He could laugh at himself—but only on his terms. A clip from a Saturday Night Live performance is exceptionally uncomfortable and unfunny. We might say this is the fault of Belushi et al, but Frank sure wasn’t helping them out.

The movie also covers the period during the ‘80s when Zappa became essentially the sole spokesperson for the world of rock and roll in the face of attempted congressional censorship of lyrics. Zappa did it because he wasn’t afraid to speak his mind, and as anyone who’s heard him talk knows, he spoke it very well indeed. Whereas most in the industry were simply too timid to stick their necks out, Zappa explained, in congressional hearings, and in interview after interview, why censorship of art was not, in fact, a good idea.

In form, the movie is well made, though rarely does it rise above what we normally get from documentaries these days. There’s a feeling that it could have been longer, included more music, been more formally daring in its construction to match the formal daring of its subject. But maybe that’s asking too much. It’s a fun ride, made not specifically for Zappa fans, but for anyone curious about this most curious of 20th century composers.

Zappa opens, at wherever they open things these sad days, on Nov. 27. Also of note, the Alamo Drafthouse On Demand is streaming a screening on Nov. 28th that includes a live Q&A with Alex Winter.